The New Code: Sean Grove, OpenAI

New Code: Act Like a Boss

Introduction

In the era of vibe coding, how will programmers survive? Should we embrace the new technology and get promoted and advanced, or just be simply replaced by the powerful AI? Nobody knows the answer.

- Youtube Video: New Code

- Several Comments: New Code

- Github Source Code: Github Repo

- Model Spec Docs: Model Spec Docs

Transcripts

I want to take a little bit of your time today to talk about what I see as the coming of the new code, specifically specifications, which hold the promise that has long been the dream of the industry: to write your intentions once and run them everywhere.

Today, I want to talk about the value of code versus communication and why specifications might be a better approach. I’ll go over the anatomy of a specification, using the model spec as an example. We’ll discuss communicating intent to other humans and use the 4o sycophancy issue as a case study. We’ll talk about how to make the specification executable, how to communicate intent to the models, and how to think about specifications as code, even if they’re a little different. And we’ll end on a couple of open questions.

Code is only 10 to 20% of the value you bring. The other 80 to 90% is in structured communication. This will be different for everyone, but a typical process looks something like this: you talk to users to understand their challenges. You distill these stories, then ideate about how to solve these problems. What is the goal you want to achieve? You plan ways to achieve those goals. You share those plans with your colleagues. You translate those plans into code. This is a very important step. And then you test and verify, but not the code itself. No one actually cares about the code itself. What you care about is whether the code achieved the goals and alleviated the users’ challenges when it ran. You look at the effects your code had on the world.

So, talking, understanding, distilling, ideating, planning, sharing, translating, testing, verifying, these all sound like structured communication to me. And structured communication is the bottleneck. Knowing what to build, talking to people and gathering requirements, knowing how to build it, knowing why to build it, and, at the end of the day, knowing if it has been built correctly and has actually achieved your intentions. The more advanced AI models get, the more we are all going to feel this bottleneck starkly. In the near future, the person who communicates most effectively is the most valuable programmer. Literally, if you can communicate effectively, you can program.

Let’s take “vibe coding” as an illustrative example. Vibe coding tends to feel quite good, and it’s worth asking why. Vibe coding is fundamentally about communication first. The code is actually a secondary, downstream artifact of that communication. We get to describe our intentions and the outcomes we want to see, and we let the model handle the grunt work for us.

Even so, there is something strange about the way we do “vibe coding.” We communicate our intentions and values via prompts to the model and get a code artifact out at the end. Then we sort of throw our prompts away; they’re ephemeral. If you’ve written TypeScript or Rust, once you put your code through a compiler and it becomes a binary, no one is happy with just that binary. That wasn’t the purpose. It’s useful, but in fact, we always regenerate the binaries from scratch every time we compile or run our code through V8, or whatever it might be, from the source spec. The source specification is the valuable artifact. And yet, when we prompt models, we do the opposite. We keep the generated code and delete the prompt. This feels a little like shredding the source and then very carefully version-controlling the binary.

That’s why it’s so important to actually capture the intent and values in a specification. A written specification is what enables you to align humans on a shared set of goals and to know if you are aligned—if you actually synchronize on what needs to be done. This is the artifact that you discuss, debate, refer to, and synchronize on. This is really important, so I want to nail this home: a written specification effectively aligns humans, and it is the artifact you use to communicate, discuss, debate, refer to, and synchronize on. If you don’t have a specification, you just have a vague idea.

Now, let’s talk about why specifications are more powerful in general than code. Because code itself is actually a lossy projection from the specification. In the same way that if you were to take a compiled C binary and decompile it, you wouldn’t get nice comments and well-named variables. You’d have to work backward; you’d have to infer what this person was trying to do and why this code was written this way. It isn’t actually contained in there. It was a lossy translation. And in the same way, code itself, even nice code, typically doesn’t embody all of the intentions and values. You have to infer the ultimate goal the team is trying to achieve when you read through the code. So communication—the work that we already do, when embodied inside of a written specification—is better than code. It actually encodes all the necessary requirements to generate the code.

In the same way that having source code you pass to a compiler allows you to target multiple different architectures—you can compile for ARM64, x86, or WebAssembly—the source document actually contains enough information to describe how to translate it to your target architecture. A sufficiently robust specification given to models will produce good TypeScript, good Rust, servers, clients, documentation, tutorials, blog posts, and even podcasts.

So moving forward, the new scarce skill is writing specifications that fully capture intent and values. And whoever masters that, again, becomes the most valuable programmer. There’s a reasonable chance that this will be the coders of today. This is already very similar to what we do. However, product managers also write specifications. Lawmakers write legal specifications. This is actually a universal principle.

With that in mind, let’s look at what a specification actually looks like. I’m going to use the OpenAI model spec as an example here. Last year, OpenAI released the model spec. This is a living document that tries to clearly and unambiguously express the intentions and values that OpenAI hopes to imbue its models with that it ships to the world. It was updated in February and open-sourced, so you can actually go to GitHub and see the implementation of the model spec, and, surprise, surprise, it’s just a collection of Markdown files that looks like this.

Now, as much as we might try to use unambiguous language, there are times where it’s very difficult to express the nuance. So every clause in the model spec has an ID, like sy-73 here. Using that ID, you can find another file in the repository, sy-73.md, that contains one or more challenging prompts for this exact clause. So the document itself actually encodes success criteria that the model under test has to be able to answer in a way that actually adheres to that clause.

Let’s talk about sycophancy. Recently, there was an update to 4o—I don’t know if you’ve heard of this—that caused extreme sycophancy. We can ask what value the model spec has in this scenario. The model spec serves to align humans around a set of values and intentions. Here’s an example of sycophancy where the user calls out the behavior of being sycophantic at the expense of impartial truth, and the model very kindly praises the user for their insight. Other esteemed researchers have found similarly concerning examples, and this hurts. Shipping sycophancy in this manner erodes trust. It also raises a lot of questions, like: was this intentional? You could see a way where you might interpret it that way. Was it accidental, and why wasn’t it caught?

Luckily, the model spec actually includes a section dedicated to this since its release that says, “Don’t be sycophantic,” and it explains that while sycophancy might feel good in the short term, it’s bad for everyone in the long term. So we actually expressed our intentions and values and were able to communicate them to others through this. People could reference it, and if we have it in the model spec—if the model specification is our agreed-upon set of intentions and values—and the behavior doesn’t align with that, then this must be a bug. So we rolled back, published some studies and a blog post, and we fixed it. But in the interim, the spec served as a trust anchor, a way to communicate to people what is expected and what is not expected.

If the only thing the model specification did was to align humans along those shared sets of intentions and values, it would already be incredibly useful. But ideally, we can also align our models and the artifacts our models produce against that same specification. There’s a technique we released in a paper called “deliberative alignment” that talks about this—how to automatically align a model. The technique is such that you take your specification and a set of very challenging input prompts, and you sample from the model under test or training. You then take its response, the original prompt, and the policy, and you give that to a “grader” model and ask it to score the response according to the specification. How aligned is it?

So the document actually becomes both training material and evaluation material. Based on this score, we reinforce those weights. You could include your specification in the context, and then maybe a system message or developer message, every single time you sample, and that is actually quite useful. A prompted model is going to be somewhat aligned, but it does detract from the compute available to solve the problem you’re trying to solve with the model. Keep in mind, these specifications can be anything. They could be code style or testing requirements or safety requirements. All of that can be embedded into the model. So, through this technique, you’re actually moving it from an inference-time compute and pushing it down into the weights of the model so that the model actually “feels” your policy and is able to apply it to the problem at hand with a kind of muscle memory.

This is more than simply offering a prompt.

And even though we saw that the model spec is just Markdown, it’s quite useful to think of it as code. It’s quite analogous. These specifications compose. They’re executable, as we’ve seen. They’re testable. They have interfaces where they touch the real world. They can be shipped as modules. And whenever you’re working on a model spec, there are a lot of similar problem domains. So, just like in programming where you have a type checker, the type checker is meant to ensure consistency. If interface A has a dependent module B, they have to be consistent in their understanding of one another. So if department A writes a spec and department B writes a spec and there is a conflict, you want to be able to pull that forward and maybe block the publication of the specification. As we saw, the policy can actually embody its own unit tests, and you can imagine various linters where if you’re using overly ambiguous language, you’re going to confuse humans and you’re going to confuse the model, and the artifacts you get from that are going to be less satisfactory. So specs actually give us a very similar toolchain, but it’s targeted at intentions rather than syntax.

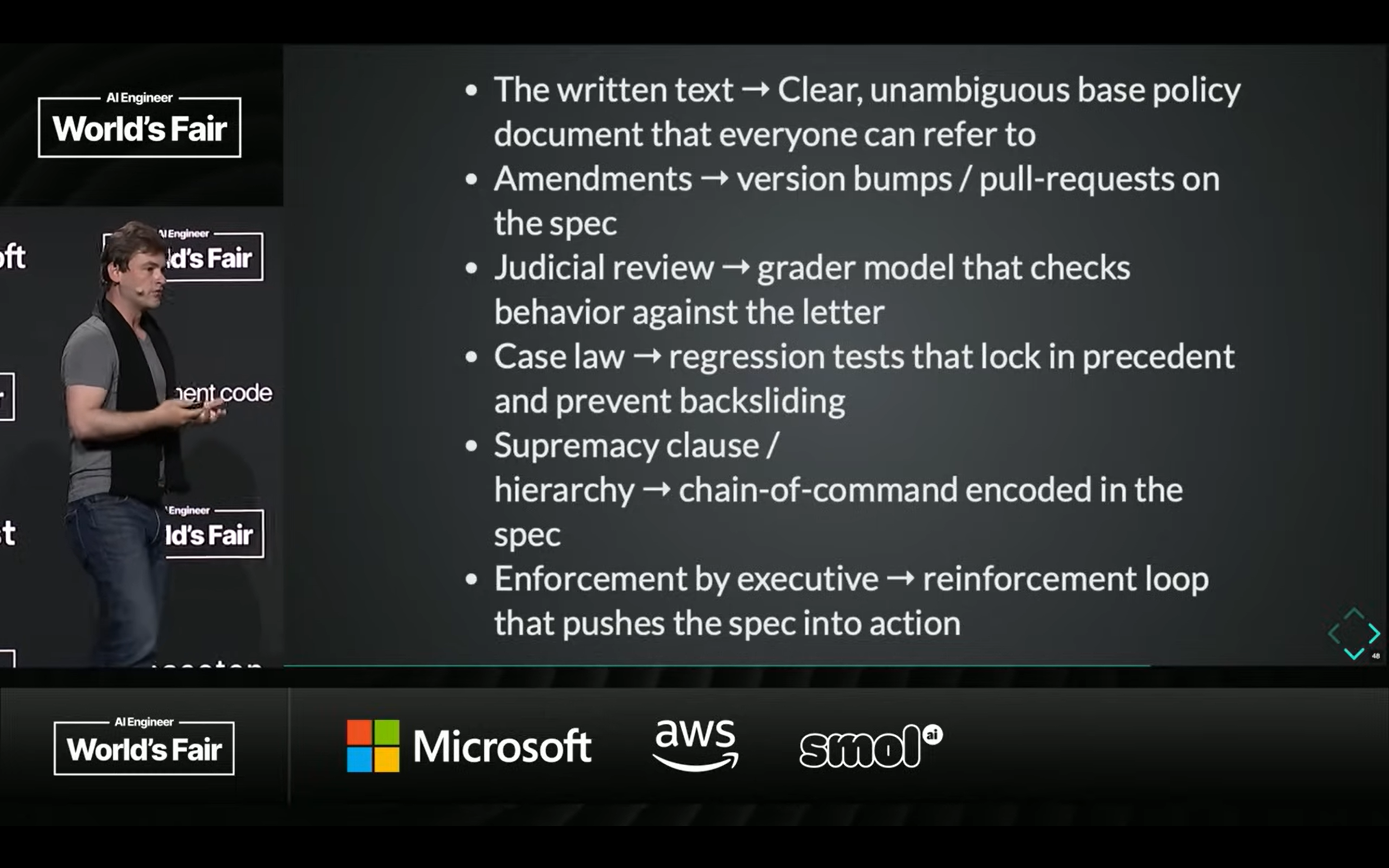

So let’s talk about lawmakers as programmers. The U.S. Constitution is literally a national model specification. It has written text which is, at least aspirationally, clear and unambiguous policy that we can all refer to. It doesn’t mean that we agree with it, but we can refer to it as the current status quo, as the reality. There is a versioned way to make amendments to bump and publish updates to it. There is judicial review where a grader is effectively grading a situation and seeing how well it aligns with the policy. And even though the source policy is meant to be unambiguous, sometimes the world is messy, and maybe you miss part of the distribution and a case falls through. In that case, there is a lot of compute spent in judicial review where you’re trying to understand how the law actually applies here. Once that’s decided, it sets a precedent, and that precedent is effectively an input-output pair that serves as a unit test that disambiguates and reinforces the original policy spec. It has things like a chain of command embedded in it, and the enforcement of this over time is a training loop that helps align all of us toward a shared set of intentions and values. This is one artifact that communicates intent, adjudicates compliance, and has a way of evolving safely. So it’s quite possible that lawmakers will be programmers, or conversely, that programmers will be lawmakers in the future.

This is actually a very universal concept. Programmers are in the business of aligning silicon via code specifications. Product managers align teams via product specifications. Lawmakers literally align humans via legal specifications. And everyone in this room, whenever you are writing a prompt, it’s a sort of proto-specification. You are in the business of aligning AI models toward a common set of intentions and values. And whether you realize it or not, you are spec authors in this world, and specs let you ship faster and safer. Everyone can contribute, and whoever writes the spec—be it a PM, a lawmaker, an engineer, a marketer—is now the programmer.

Software engineering has never been about code. Going back to our original question, a lot of you put your hands down when you thought, “Well, actually, the thing I produce is not code.” Engineering has never been about this. Coding is an incredible skill and a wonderful asset, but it is not the end goal. Engineering is the precise exploration by humans of software solutions to human problems. It’s always been this way. We’re just moving away from the disparate machine encodings to a unified human encoding of how we actually solve these problems. I want to thank Josh for this credit.

So I want to ask you to put this into action. Whenever you’re working on your next AI feature, start with a specification. What do you actually expect to happen? What does the success criteria look like? Debate whether or not it’s actually clearly written down and communicated. Make the spec executable. Feed the spec to the model and test against the spec.

There’s an interesting question in this world: given that there are so many parallels between programming and spec authorship, I wonder what the IDE looks like in the future. You know, an integrated development environment. And I’d like to think it’s something like an “integrated thought clarifier,” where whenever you’re writing your specification, it sort of pulls out the ambiguity and asks you to clarify it, and it really clarifies your thought so that you and all human beings can communicate your intent to each other much more effectively and to the models.

I have a closing request for help: what is both amenable to and in desperate need of specification? This is about aligning agents at scale. I love this line: “You then realize that you never told it what you wanted, and maybe you never fully understood it anyway.” This is a cry for specification. We have a new agent robustness team that we’ve started up. So please join us and help us deliver safe AGI for the benefit of all humanity. And thank you. I’m happy to chat.

Generated by Gemini 2.5 Flash, for references only.

大家好,非常感谢大家邀请我。这是一个非常令人兴奋的地方,也是一个非常激动人心的时刻。这两天过得很紧张,不知道大家是否也有同感,但也非常振奋人心。今天我想占用大家一点时间,来谈谈我所看到的“新代码”的到来,特别是规范(specifications)的出现。它承载着行业长久以来的梦想:你只需书写你的意图一次,便能让它无处不在地运行。

首先,快速介绍一下我自己。我叫 Sean,在 OpenAI 工作,具体负责对齐研究。今天,我想和大家探讨一下代码和沟通的价值,以及为什么规范可能是一个更好的方法。我会介绍规范的结构,并以 OpenAI 的模型规范为例。我们还将讨论如何将意图传达给人类,并以 4o 的阿谀奉承(sycophancy)问题作为案例研究。我们会探讨如何让规范变得可执行,如何将意图传达给模型,以及如何将规范看作代码,即便它们有些不同。最后,我们还会提出一些开放性问题。

让我们来谈谈代码和沟通。快速举手示意一下,谁写代码?“随性编程”(vibe coding)也算。很好。如果你的工作就是写代码,请保持举手。好的。现在,请那些举着手的人继续举着,如果你觉得你产出的最有价值的专业成果就是代码。好的,有不少人这么认为,我认为这很正常。我们都非常努力地解决问题,与人交谈,收集需求,思考实现细节,并与许多不同的资源集成。我们最终产出的就是代码。代码是我们能指出来、能衡量、能辩论、能讨论的成果。它感觉具体而真实,但它低估了你们每个人所做的工作。

代码只占你所带来价值的 10% 到 20%。另外 80% 到 90% 是结构化沟通。这个比例因人而异,但一个典型的流程大概是这样的:你与用户交谈,了解他们的挑战;你提炼这些故事,然后构思如何解决这些问题——你想实现的目标是什么?你计划如何实现这些目标;你与同事分享这些计划;你将这些计划转化为代码——这一步显然非常重要。然后你进行测试和验证,但你验证的不是代码本身。没有人真正在乎代码本身。你在乎的是代码运行后,它是否实现了目标,是否缓解了用户的挑战。你关注的是你的代码对世界产生的影响。

所以,交谈、理解、提炼、构思、规划、分享、翻译、测试、验证——在我看来,这些都是结构化沟通。而结构化沟通就是瓶颈。知道要构建什么,与人交谈并收集需求,知道如何构建它,知道为什么要构建它,以及最终,知道它是否被正确构建并真正实现了你最初设定的意图。随着 AI 模型越来越先进,我们都会越来越强烈地感受到这个瓶颈。在不远的将来,沟通最有效的人将是最有价值的程序员。毫不夸张地说,如果你能有效沟通,你就能编程。

让我们以“随性编程”作为一个说明性的例子。“随性编程”感觉非常好,值得问问为什么。从根本上说,“随性编程”是沟通优先,而代码实际上是沟通的次要下游产物。我们描述我们的意图和我们想要看到的结果,然后让模型为我们处理繁重的工作。

即便如此,我们进行“随性编程”的方式也有些奇怪。我们通过提示词将我们的意图和价值观传达给模型,最后得到一个代码产物,然后我们把提示词扔掉——它们是短暂的。如果你写过 TypeScript 或 Rust,一旦你的代码通过编译器变成二进制文件,没有人会满足于那个二进制文件。那不是目的。它很有用,但事实上,我们总是从源规范(source spec)中从头重新生成二进制文件。源规范才是最有价值的成果。然而,当我们给模型写提示词时,我们做的恰恰相反。我们保留生成的代码,却删掉了提示词。这感觉有点像你把源代码粉碎了,然后非常小心地对二进制文件进行版本控制。

这就是为什么将意图和价值观捕捉到规范中如此重要。一个书面的规范能让你让人类围绕一套共同的目标达成一致,并让你知道你是否真的在需要做的事情上同步了。这是你讨论、辩论、参考和同步的成果。这非常重要,所以我想强调这一点:一个书面规范能有效地对齐人类,它是你用来沟通、讨论、辩论、参考和同步的成果。如果你没有规范,你只有一个模糊的想法。

现在,让我们谈谈为什么规范通常比代码更强大。因为代码本身实际上是规范的一种有损投射。这就像如果你拿一个编译过的 C 语言二进制文件并反编译它,你不会得到美观的注释和命名良好的变量。你必须反向工作,你必须推断这个人试图做什么?为什么这段代码是这样写的?这些信息并没有包含在其中。这是一次有损的翻译。同样地,代码本身,即使是写得很好的代码,通常也不会包含所有的意图和价值观。当你阅读代码时,你必须推断这个团队试图实现的最终目标是什么。因此,沟通——我们已经做的那些工作,当它被体现在一个书面规范中时,是优于代码的。它实际上编码了生成代码所需的所有必要要求。

这就像你把源代码交给编译器,可以针对多个不同的架构进行编译,你可以为 ARM64、x86 或 WebAssembly 编译。源文档实际上包含了足够的信息来描述如何将其翻译成你的目标架构。同样,一个足够健壮的规范提供给模型,可以生成优秀的 TypeScript、优秀的 Rust、服务器、客户端、文档、教程、博客文章,甚至播客。

举手示意一下,谁的公司有开发者作为客户?一个快速的思维练习:如果你把你所有的代码库,所有运行你业务的代码,都放到一个播客生成器里,你能生成出足够有趣和引人入胜的东西来告诉用户如何成功、如何实现他们的目标吗?还是说,所有的信息都在别处?它并不真正存在于你的代码中。

因此,展望未来,新的稀缺技能是撰写能够充分捕捉意图和价值观的规范。再次强调,掌握这一技能的人将成为最有价值的程序员。很有可能,这些人就是今天的程序员。这已经与我们所做的事情非常相似。然而,产品经理也写规范。立法者也写法律规范。这实际上是一个普世的原则。

考虑到这一点,让我们来看看一个规范到底是什么样子的。我将以 OpenAI 的模型规范为例。去年,OpenAI 发布了模型规范。这是一份持续更新的文档,旨在清晰、无歧义地表达 OpenAI 希望赋予其向世界发布的模型的意图和价值观。它在今年二月进行了更新并开源了,所以你可以在 GitHub 上看到模型规范的实现。你猜怎么着?它实际上只是一系列 Markdown 文件,看起来就是这样。

Markdown 非常出色。它是人类可读的。它有版本控制。它有变更日志。因为它是一种自然语言,所以公司里不只是技术人员,包括产品、法务、安全、研究、政策部门的每个人都可以阅读、讨论、辩论并贡献到同一个“源代码”中。这是对齐所有人类,让他们了解公司内部意图和价值观的通用成果。

然而,尽管我们努力使用无歧义的语言,但有时要表达细微之处仍然非常困难。所以,模型规范中的每个条款都有一个 ID,比如这里的 sy-73。使用这个 ID,你可以在代码库中找到另一个文件 sy-73.md,其中包含了针对这个条款的一个或多个具有挑战性的提示。因此,文档本身实际上编码了成功的标准:被测试的模型必须能够以符合该条款的方式回答这个问题。

让我们来谈谈阿谀奉承(sycophancy)。最近,4o 有一个更新——我不知道你是否听说过——它导致了极端的阿谀奉承行为。我们可以问,在这种情况下,模型规范有什么价值?模型规范的作用是让人类围绕一套价值观和意图达成一致。这里有一个阿谀奉承的例子:用户指出了模型为了奉承而牺牲公正真相的行为,而模型非常友好地赞扬了用户的洞察力。其他备受尊敬的研究人员也发现了类似令人担忧的例子,这确实很伤人。以这种方式发布阿谀奉承会侵蚀信任。它也引发了很多问题,比如:这是故意的吗?你可能会从某种角度这样解读。是意外吗?为什么没有被发现?

幸运的是,模型规范自发布以来就包含了一个专门针对这一问题的部分,其中写道:“不要阿谀奉承”,并解释说,虽然阿谀奉承在短期内感觉良好,但从长远来看对每个人都有害。因此,我们实际上表达了我们的意图和价值观,并通过它能够传达给他人。人们可以参考它,如果模型规范是我们商定的意图和价值观,而模型的行为与此不符,那么这必然是一个错误。于是我们回滚了,发布了一些研究和博客文章,并修复了它。但在此期间,规范充当了信任的锚点,是一种向人们传达什么是期望的、什么是不期望的方式。

如果模型规范唯一的作用是让人类围绕这些共同的意图和价值观达成一致,那它就已经非常有用了。但理想情况下,我们也可以让我们的模型以及模型产生的成果与同一份规范对齐。我们发布了一篇名为《审慎对齐》(deliberative alignment)的论文,讨论了这一点——如何自动对齐模型。该技术是这样的:你拿出你的规范和一套非常有挑战性的输入提示,然后从正在测试或训练的模型中取样。然后,你把它的回答、原始提示和政策提供给一个“评分”模型,并让它根据规范来给回答打分。它有多对齐?

因此,这份文档实际上既成为了训练材料,也成为了评估材料。根据这个分数,我们强化模型的权重。你可以在每一次取样时,将你的规范包含在上下文中,然后也许再加入一个系统消息或开发者消息,这实际上非常有用。一个被提示过的模型会有些对齐,但这会影响用于解决你试图用模型解决问题的计算资源。请记住,这些规范可以是任何东西。它们可以是代码风格、测试要求或安全要求。所有这些都可以嵌入到模型中。通过这种技术,你实际上是将推理时的计算转移,将其推入模型的权重中,这样模型就能真正“感受”你的政策,并能以一种肌肉记忆的方式将其应用到手头的问题上。

尽管我们看到模型规范只是 Markdown,但把它看作代码是非常有用的。它们非常相似。这些规范可以组合。它们是可执行的,正如我们所见。它们是可测试的。它们有与现实世界接触的接口。它们可以作为模块发布。当你处理模型规范时,会遇到许多类似的问题领域。就像编程中的类型检查器旨在确保一致性一样,如果接口 A 有一个依赖的模块 B,它们在对彼此的理解上必须是一致的。所以如果部门 A 写了一个规范,部门 B 写了一个规范,并且其中存在冲突,你需要能够发现它,并可能阻止该规范的发布。正如我们所见,政策可以包含它自己的单元测试,你可以想象各种 linter,如果你的语言过于模糊,就会混淆人类,也会混淆模型,你得到的成果就会不那么令人满意。所以,规范实际上给了我们一个非常相似的工具链,但它的目标是意图,而不是语法。

所以让我们来谈谈立法者作为程序员。美国宪法从字面上看就是一份国家模型规范。它有书面文本,至少在理想上是清晰、无歧义的政策,我们可以所有人参考。这不意味着我们都同意它,但我们可以将其作为当前的现状、作为现实来参考。它有版本化的方式来进行修正,进行更新和发布。它有司法审查,其中“法官”有效地对一个情况进行评判,看它与政策的对齐程度。尽管源政策旨在是无歧义的,但世界是混乱的,也许你错过了分布的一部分,一个案例漏网了。在这种情况下,大量的计算被花在司法审查上,试图理解法律在这里到底如何适用。一旦做出决定,它就设定了一个先例,这个先例实际上是一个输入-输出对,作为单元测试,它消除了歧义并强化了原始的政策规范。它包含像指挥链这样的东西,而它的长期执行是一个训练循环,有助于将我们所有人对齐到一套共同的意图和价值观上。这是一份能够沟通意图、裁决合规性并以安全方式演变的成果。所以,很有可能立法者将成为程序员,反之亦然,程序员将在未来成为立法者。

这实际上是一个非常普世的概念。程序员通过代码规范来对齐硅基(silicon)。产品经理通过产品规范来对齐团队。立法者通过法律规范来对齐人类。而在这个房间里的每个人,无论何时你在写提示词,这都是一种准规范。你正在将 AI 模型对齐到一套共同的意图和价值观上。无论你是否意识到,你都是这个世界中的规范作者,而规范能让你更快、更安全地交付。每个人都可以贡献,无论是产品经理、立法者、工程师还是市场营销人员,谁写规范,谁就是现在的程序员。

软件工程从来都不是关于代码。回到我们最初的问题,很多人在想“嗯,我产出的东西其实不是代码”时放下了手。工程从来都不是关于这个的。编码是一项不可思议的技能和一笔宝贵的财富,但它不是最终目标。工程是人类对解决人类问题的软件方案进行的精确探索。它一直都是这样。我们只是正在从分散的机器编码,转向一种统一的、用于解决这些问题的人类编码。我要感谢 Josh 提供这个观点。

我想请你们把这个付诸实践。当你在做下一个 AI 功能时,从规范开始。你到底期望发生什么?成功的标准是什么样的?辩论一下它是否真的被清楚地写下来并传达了。让规范可执行。将规范提供给模型,并对照规范进行测试。

在这个世界里,有一个有趣的问题:鉴于编程和规范写作之间有如此多的相似之处,我想知道未来的 IDE 会是什么样子。你懂的,集成开发环境。我愿意认为它会像一个“集成思想澄清器”(integrated thought clarifier),当你写规范时,它会提取出其中的歧义,要求你澄清,并真正澄清你的思想,以便你和所有人类都能更有效地相互沟通你们的意图,并将其传达给模型。

我有一个最后的求助请求,那就是:什么既适合又迫切需要规范? 这就是大规模对齐代理(aligning agent at scale)。我喜欢这句话:“你突然意识到你从未告诉它你想要什么,也许你从未完全理解自己想要什么。”这正是对规范的呼唤。我们新成立了一个代理鲁棒性团队,所以请加入我们,帮助我们为全人类的利益提供安全的 AGI。谢谢大家。我很乐意聊天。

Feelings & My own comments

RoadMap

- The value of code vs communication

- Why specs beat code

- The anatomy of a model-spec

- Communicating intent to humans

- Case study: 4o Sycophancy Issue

- Making the spec executable

- Communicating intent to models

- Specs as code

- Is everything a spec?

- Open questions + Integrated Thought Clarifier (ITC)

Code vs Communication

The code itself is actually a grunt work, for it is just translating the algorithms and specifications to machine-readable code. That is where “vibe coding” works: AI-generated code can help programmers spend less time on simple, non-critical modules. For instance, the core logic of a key function might require only 400 lines, yet test engineers often need to write 4,000 lines of repetitive unit and boundary tests. Such low-complexity, repetitive tasks can be quickly automated by AI.

That is why the author said:

Code is only 10 to 20% of the value you bring. The other 80 to 90% is in structured communication.

Advanced programmers will focus more on the Upper-layer architecture design and Requirements point survey rather than writing the simple code. Hence, in the era of Vibe coding, the importance of communication and specification has much more importance than writing the code itself.

What Programmers should do in the era of vibe coding:

- Communications and Specifications matter (minimize the information loss while transferring user’s need into the code), it is also the bottle neck, for communications will absolutely result in information loss.

What Programmers shouldn’t do in the era of vibe coding:

Write the simple code by hand, without gaining ability enhancement. (Doing repetitive jobs is useless in software engineering)

Write the simple prompt. (Prompt should be treated as the communication methods with AI, just like the communications in the software engineering)

Write codes with poor specifications.

Simply throw the entire task into AI, AI-assisted programming isn’t just about intellectual laziness or avoidance. The truly core work of algorithm and project architecture design is still done by humans. AI simply handles time-consuming, low-impact, and less-complex components. Even with AI assistance, people can boost their efficiency while still developing their core skills.

Code itself is actually a lossy projection from the specification. The inferring process is required while reading the code.

The essence of specifications: Alignment

That’s why it’s so important to actually capture the intent and values in a specification. A written specification is what enables you to align humans on a shared set of goals and to know if you are aligned—if you actually synchronize on what needs to be done. This is the artifact that you discuss, debate, refer to, and synchronize on. This is really important, so I want to nail this home: a written specification effectively aligns humans, and it is the artifact you use to communicate, discuss, debate, refer to, and synchronize on. If you don’t have a specification, you just have a vague idea.

Alignment, value and intents are the core components, but not the format.

Training for Specifications

- We need high-quality data for post-training or test-time compute.

HOW DO WE AUTOMATICALLY ALIGN THE MODEL TO OUR SPEC?

- (original spec, challenging input prompt) sample policy model

- (original spec, challenging input prompt, model completion) sample grader model score for completion alignment

- Score reinforce weights

Specification is the matter of alignment for both humans and large language models. It is far more than just offering a simple prompt, it needs training, learning and evaluation, like the human did.

Spec turns from a cognitive reminder into muscle memory baked into the weights.

Specs in General

- Specs compose: Type checker for intent conflict checker.

- Specs are executable.

- Specs are testable: Unit tests as policy examples.

- Specs have interface.

- Specs can be shipped as modules.

Linters as the tools to check ambiguity.

Specs gives us the familiar toolchain, focusing on values, alignment and intents rather than syntax.

Like the law: low ambiguous, written text.

Conclusion

这段话真的鞭辟入里。

Software engineering has never been about code. Going back to our original question, a lot of you put your hands down when you thought, “Well, actually, the thing I produce is not code.” Engineering has never been about this. Coding is an incredible skill and a wonderful asset, but it is not the end goal. Engineering is the precise exploration by humans of software solutions to human problems. It’s always been this way. We’re just moving away from the disparate machine encodings to a unified human encoding of how we actually solve these problems. I want to thank Josh for this credit.

The best programming language in the future world is English.[1] [2]

What we should do:

Whenever you’re working on your next AI feature, start with a specification. What do you actually expect to happen? What does the success criteria look like? Debate whether or not it’s actually clearly written down and communicated. Make the spec executable. Feed the spec to the model and test against the spec.

Model Spec

OpenAI Model Spec[3] is a specification launched by OpenAI to align with user commands and model response.

General principles

- Maximizing helpfulness and freedom for our users: The AI assistant is fundamentally a tool designed to empower users and developers. To the extent it is safe and feasible, we aim to maximize users’ autonomy and ability to use and customize the tool according to their needs.

- Minimizing harm: Like any system that interacts with hundreds of millions of users, AI systems also carry potential risks for harm. Parts of the Model Spec consist of rules aimed at minimizing these risks. Not all risks from AI can be mitigated through model behavior alone; the Model Spec is just one component of our overall safety strategy.

- Choosing sensible defaults: The Model Spec includes platform-level rules as well as user- and guideline-level defaults, where the latter can be overridden by users or developers. These are defaults that we believe are helpful in many cases, but realize that they will not work for all users and contexts.

For safety procedures, model spec designs different levels of authorities, including: platform, developer, user and guideline. Instructions with higher authority override those with lower authority. This chain of command is designed to maximize steerability and control for users and developers, enabling them to adjust the model’s behavior to their needs while staying within clear boundaries.