Pre-Training-Is-Dead?

Neurips Speeches: Pretraining is Dead?

Introduction

I originally intended to write this blog in December, but Ilya’s views faced a lot of opposition at that time. However, in just three months, the emergence of Deepseek and the explosive growth of the AI agent sector seem to validate the correctness of this speech. In this blog, I will analyze, from the current perspective, the shift in the development path of AI starting from scaling laws, and interpret Ilya’s predictions for future development prospects.

The transcripts are copied from here[2], and you can go through YouTube for the original video[1].

Table of contents

- 0:00:00 NeurIPS Then and Now

- 0:00:30 A Ten Year Retrospective

- 0:01:22 The Scaling Hypothesis: Neural Network History

- 0:05:58 Connectionism: The Foundation of Deep Learning

- 0:09:51 Scaling in Biology: Body Size and Brain Mass

- 0:16:45 Beyond Neurons: New Frontiers in Cognition

- 0:16:59 Biological Inspiration in AI: Limited but Successful

- 0:18:12 AI Reasoning, Hallucinations, and Rights

- 0:22:13 Multi-hop reasoning and distribution generalization

A Ten Year Retrospective

And now we've got my experienced, hopefully visor. But here I'd like to talk a little bit about the work itself and maybe a ten year retrospective on it. Because a lot of the things in this work were correct, but some not so much. And we can review them and we can see what happened and how it gently flowed to where we are today.

The Scaling Hypothesis: Neural Network History

So let's begin by talking about what we did. And the way we'll do it is by showing slides from the same talk 10 years ago. But the summary of what we did is the following three bullet points.

- Autoregressive model trained on text.

- Large neural networks.

- Large dataset.

And what we said here is that if you have a large neural network with 10 layers, then it can do anything that a human being can do in a fraction of a second.

Well, if you believe the deep learning dogma, so to say, that artificial neurons and biological neurons are similar, or at least not too different. And you believe that real neurons are slow, then anything that we can do quickly. By we, I mean human beings. I even mean just one human in the entire world. If there is one human in the entire world that can do some task in a fraction of a second, then a 10 layer neural network can do it too. Right? It follows. You just take their connections and you embed them inside your neural net, the artificial one.

If you could go beyond in your layers somehow, then you could do more. But back then, we could only do 10 layers, which is why we emphasized whatever human beings can do in a fraction of a second.

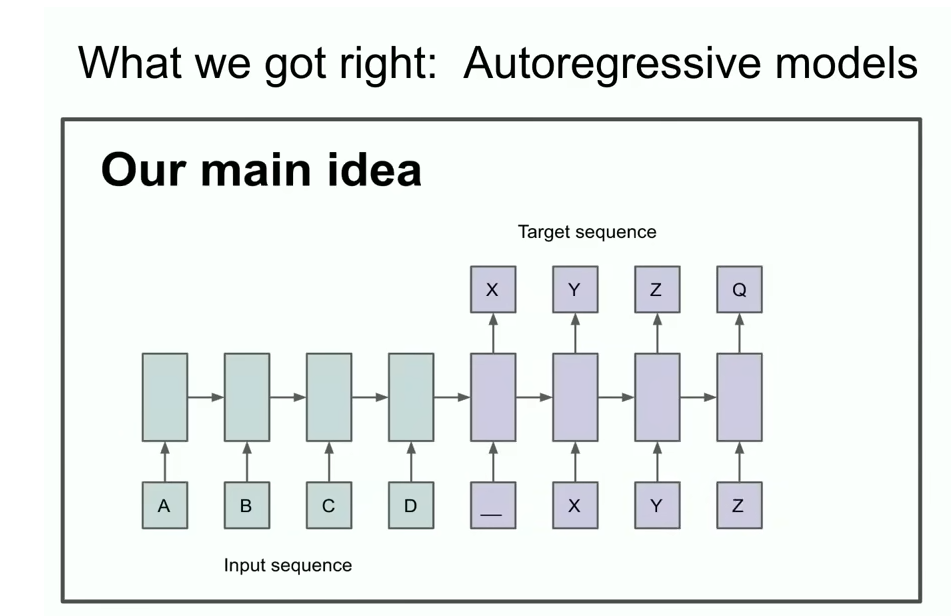

A different slide from the talk. You might be able to recognize that something auto-regressive is going on here. The slide says that if you have an auto-regressive model and it predicts the next token well enough, then it will in fact grab and capture and grasp the correct distribution over sequences that come next. And this was a relatively new thing. It wasn't literally the first ever auto-regressive neural network, but I would argue it was the first auto-regressive neural network where we really believed that if you train it really well, then you will get whatever you want.

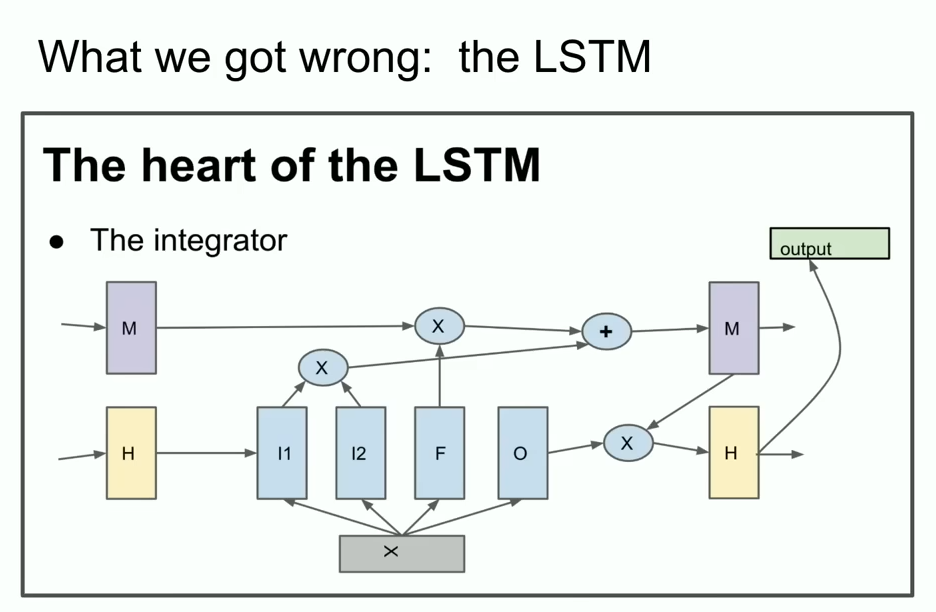

Now I'm going to show you some ancient history that many of you may have never seen before. It's called the LSTM. To those unfamiliar, an LSTM is the thing that poor deep learning researchers did before Transformers. And it's basically a ResNet, but rotated 90 degrees.

Another cool feature from that old talk that I want to highlight is that we used parallelization. But not just any parallelization. We used pipelining, as witnessed by this one layer per GPU. Was it wise to pipeline? As we now know, pipelining is not wise. But we were not as wise back then. So we used that and we got a 3.5x speedup using eight GPUs.

And the conclusion slide in some sense, the conclusion slide from the talk from back then is the most important slide because it spelled out what could arguably be the beginning of the scaling hypothesis, right? That if you have a very big data set and you train a very big neural network, then success is guaranteed.

Maybe this is the prototype of Scaling Law! Without considering the limitation of data and computing resources (at least we have Moore’s Law), the model’s accuracy can be guaranteed by increasing the number of parameters and the training cost. In other world, the more parameters the model have, the more powerful the model it is, if given enough training resources.

This answer is cruel, but somehow effectiveness.

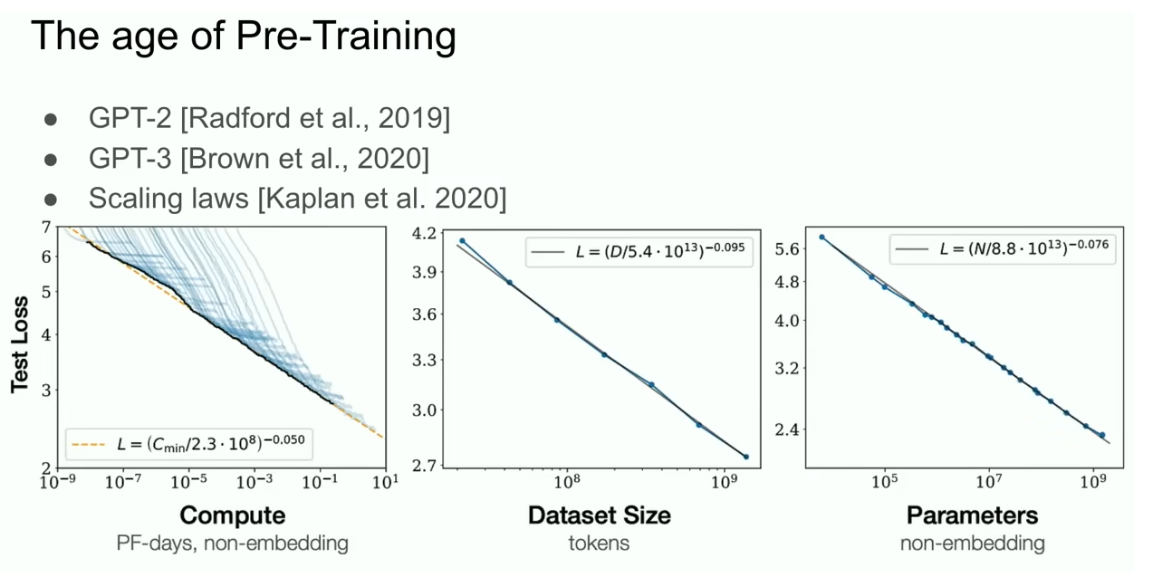

The age of Pre-Training

But what this led to the age of pre-training. And the age of pre-training is what we might say the GPT-2 model, the GPT-3 model, the scaling laws. And I want to specifically call out my former collaborators, Alec Radford, also Jared Kaplan, Dario Amode, for really making this work. And this is what's been the driver of all of progress, all the progress that we see today. Extra-large neural networks. Extra-ordinarily large neural networks trained on huge data sets.

But pre-training as we know it will unquestionably end. Pre-training will end. Why will it end? Because while compute is growing through better hardware, better algorithms, and larger clusters, all those things keep increasing your compute. All these things keep increasing your compute. The data is not growing because we have but one internet. We have but one internet. You could even say, you could even go as far as to say that data is the fossil fuel of AI. It was like created somehow, and now we use it, and we've achieved peak data, and there will be no more.

What comes next?

So, here I'll take a bit of liberty to speculate about what comes next. Actually, I don't need to speculate because many people are speculating too. And I'll mention their speculations. You may have heard the phrase agents. It's common. And I'm sure that eventually something will happen. But people feel like something agents is the future. More concretely, but also a little bit vaguely, synthetic data. But what does synthetic data mean? Figuring this out is a big challenge. And I'm sure that different people have all kinds of interesting progress there. And an inference time compute, or maybe what's been most recently, most vividly seen in O1, the O1 model. These are all examples of things, of people trying to figure out what to do after pretraining. And those are all very good things to do.

- Agents

- Synthetic Data

- Inference time compute

Scaling in Biology: Body Size and Brain Mass

I want to mention one other example from biology, which I think is really cool. What that means is that there is a precedent. There is an example of biology figuring out some kind of different scaling. Something clearly is different. So, I think that is cool.

In the long term…

Super Intelligence

- Agentic

Those systems are actually going to be agentic in real ways. Whereas right now, the systems are not agents in any meaningful sense. Just very, that might be too strong. They are very, very slightly agentic. Just beginning.

- Reasons

It will actually reason. And by the way, I want to mention something about reasoning. Is that a system that reasons, the more it reasons, the more unpredictable it becomes. The more it reasons, the more unpredictable it becomes. All the deep learning that we've been used to is very predictable. Because if you've been working on replicating human intuition essentially. It's like the gut feel. If you come back to the 0.1 second reaction time. What kind of processing we do in our brains? Well, it's our intuition. So we've endowed our AIs with some of that intuition. But reasoning, and you're seeing some early signs of that. Reasoning is unpredictable. And one reason to see that is because the chess AIs, the really good ones, are unpredictable to the best human chess players.

So we will have to be dealing with AI systems that are incredibly unpredictable. They will understand things from limited data. They will not get confused. All the things which are really big limitations.

In the Q&A part: About reasoning and hallucinations

You mentioned reasoning as being one of the core aspects of maybe the modeling in the future. And maybe a differentiator. What we saw in some of the poster sessions is that hallucinations in today’s models, the way we’re analyzing… I mean, maybe you correct me. You’re the expert on this. But the way we’re analyzing whether a model is hallucinating today without… Because we know of the dangers of models not being able to reason, that we’re using a statistical analysis. Let’s say some amount of standard deviations or whatever away from the mean. In the future, wouldn’t it… Do you think that a model given reasoning will be able to correct itself, sort of autocorrect itself? And that will be a core feature of future models so that there won’t be as many hallucinations because the model will recognize when… Maybe that’s too esoteric of a question. But the model will be able to reason and understand when a hallucination is occurring. Does the question make sense?

Yes, the answer is yes!

I'm not saying how, by the way. And I'm not saying when. I'm saying that it will.

- Self-awareness

And when all those things will happen together with self-awareness. Because why not? Self-awareness is useful. You, ourselves, are parts of our own world models. When all those things come together. We will have systems of radically different qualities and properties that exist today. And of course, they will have incredible and amazing capabilities. But the kind of issues that come up with systems like this. And I'll just leave it as an exercise to imagine. It's very different from what we are used to.

Q&A Part

Q: Now, in 2024, are there other biological structures that are part of human cognition that you think are worth exploring in a similar way or that you’re interested in anyway?

So, the way I'd answer this question is that if you are or someone is a person who has a specific insight about, hey, we are all being extremely silly because clearly the brain does something and we are not. And that's something that can be done and that's something that can be done and they should pursue it. I personally don't. Well, it depends on the level of abstraction you're looking at. Maybe I'll answer it this way. Like there's been a lot of desire to make biologically inspired AI. And you could argue on some level that biologically inspired AI is incredibly successful, which is all of deep learning is biologically inspired AI. But on the other hand, the biological inspiration was very, very, very modest. It's like, let's use neurons. This is the full extent of the biological inspiration. Let's use neurons. And more detailed biological inspiration has been very hard to come by. But I wouldn't rule it out. I think if someone has a special insight, they might be able to see something and that would be useful.

Q: I wanted to ask, do you think LLMs generalize multi-hop reasoning out of distribution?

So, okay. The question assumes that the answer is yes or no. But the question should not be answered yes or no. Because what does it mean, out of distribution generalization? What does it mean? What does it mean in distribution? And what does it mean out of distribution? Because it's a test of time talk, I'll say, that long, long ago, before people were using deep learning, they were using things like string matching, n-grams. For machine translation, people were using statistical phrase tables. Can you imagine? They had tens of thousands of code of complexity, which was, I mean, it was truly unfathomable. And back then, generalization meant, is it literally not in the same word phrasing as in the data set? Now, we may say, well, sure, my model achieves this high score on, I don't know, math competitions. But maybe the math, maybe some discussion in some forum on the internet was about the same ideas, and therefore it's memorized. Well, okay, you could say maybe it's in distribution, maybe it's memorization. But I also think that our standards for what counts as generalization have increased really quite substantially, dramatically, unimaginably, if you keep track. And so I think the answer is, to some degree, probably not as well as human beings. I think it is true that human beings generalize much better. But at the same time, they definitely generalize out of distribution to some degree.

Other Lectures about Pre-training and Scaling Law

Jason Wei: Scaling Paradigms for Large Language Models

The original video on Youtube is here.[5]

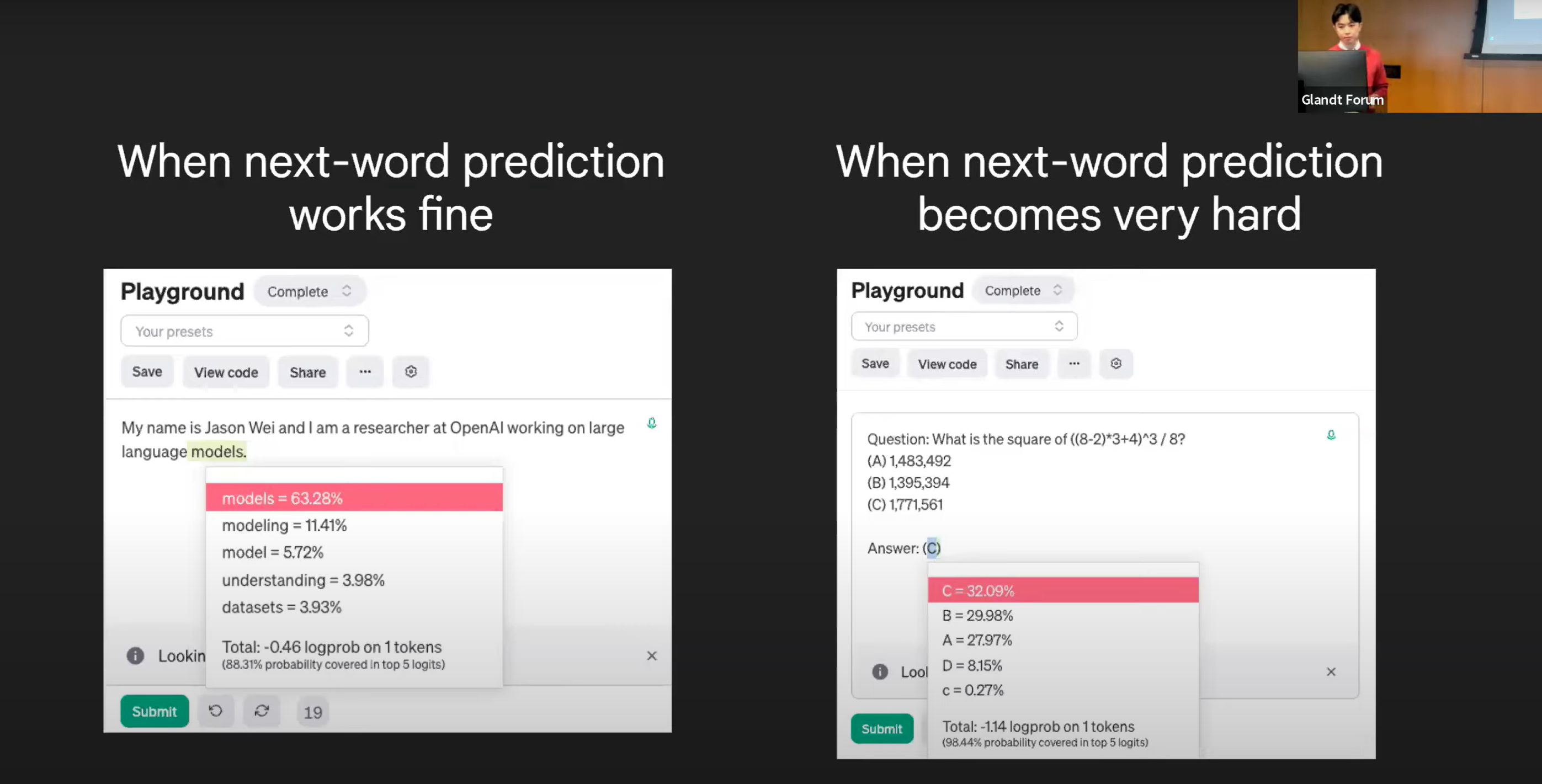

The scaling paradigms for next-word predictions works so well, but is it all we need to achieve AGI? Maybe not, Jason Wei gives his reasons in the text below:

Some words may be super hard for next-token predictions to implement.

In pure-next-token prediction, the model sees language as a pure probablility of language distribution, it means the model uses similar computing resources to solve hard tasks and easier ones.

The approach: Chain of Thought Prompting.

The limitation of CoT: We want the model’s chain of thought to be my inner monologue or like a stream of thought.

All in all, only the “dumb” scaling law is not correct in the long run! We need to find something for effective, rather than naive. Maybe is LLM reasoning.

Shital Shah’s comment on scaling law…

The whole transcripts

With current synthetic data techniques, one issue is that they don’t add a lot of new entropy to the original pre-training data. Pre-training data is synthesized from spending centuries of human-FLOPs. Prompt-based synthetic generation can only produce data in the neighborhood of existing data. This creates an entropy bottleneck: there is simply not enough entropy per token to gain as you move down the tail of organic data or rely on prompt-based synthetic data.

A possible solution is to spend more compute time during testing to generate synthetic data with higher entropy content. The entropy per token in a given dataset seems to be related to the FLOPs spent on generating that data. Human data was generated from a vast amount of compute spent by humans over millennia. Our pre-training data is the equivalent of fossil fuel, and that data is running out.

While human-FLOPs are in limited supply, GPU-FLOPs through techniques like ttc can allow us to generate synthetic data with high entropy, offering a way to overcome this bottleneck. However, the bad news is that we will need more compute than predicted by scaling laws. So, can’t we just rely solely on task-targeted compute?

Merely scaling inference compute won’t be sufficient. A weak model can spend an inordinate amount of inference compute and still fail to solve a hard problem. There seems to be an intricate, intertwined dance between training and inference compute, with each improving the other. Imagine a cycle of training a model, generating high-entropy synthetic data by scaling inference compute, and then using that data to continue training. This is the self-improving recipe.

Humans operate in a similar way: we consume previously generated data and use it to create new data for the next generation. One critical element in this process is embodiment, which enables the transfer of entropy from our environment. Spend thousands of years of human-FLOPs in this way, and you get the pre-training data that we currently use!

Neurips 2024 speech delivered by Kaiming He

ML Research, via the Len

- Research is SGD in a chaotic landscape

- Look for ‘surprise’

- Future is the Real Test set

- Scalability

The files stores in here.

References

- the original videos ↩

- speech’s scripts ↩

- https://www.reddit.com/r/singularity/comments/1hdrjvq/ilyas_full_talk_at_neurips_2024_pretraining_as_we/ ↩

- Remarks by luluyan ↩

- Jason Wei: Scaling Paradigms for Large Language Models ↩

Scaling laws assume that the quality of tokens remains mostly the same as you scale. However, in real-world large-scale datasets, this is not true. When there is an upper bound on quality training tokens, there is an upper bound on scaling. But what about synthetic data?

↩- https://x.com/sytelus/status/1857102074070352290 ↩